I can’t remember the last time I made a New Year’s resolution, though I readily admit it’s a tempting time for a personal “reset” or goal-setting exercise. A little self-delusion can’t hurt.

Organizations can feel the itch, too. In extreme form, it’s known in corporate-speak as “setting stretch goals.” Popularized by Jack Welch of General Electric, stretch goals are loosely defined as aspirational targets seemingly impossible to reach with current capabilities; they are designed to jolt organizations out of complacency and into exploration and innovation.

Good idea or bad? Those in the pro camp say stretch goals focus attention on the future, spark energy, and increase organization-wide performance (“high aspirations can often contribute to high achievement,” is how one expert puts it). A great example is the case of Southwest Airlines, which set a seemingly outlandish target of 10-minute turnaround times at airport gates. The goal was eventually achieved when airline managers, in a spark of divergent thinking, adapted techniques used by race car pit crews.

The detractors counter that stretch goals foster unethical behaviour, lead to excessive risk-taking, and are demotivating when they seem overwhelming.

There’s no shortage of anecdotes but little hard-core evidence that stretch goals actually work. To fill that void, researchers Sitkin (Duke U), See (New York U), Miller (U Houston), Lawless (U Maryland), and Carton (Penn State U) took a deeper look at how stretch goals can influence learning and performance, incorporating the latest thinking about organizational goal-setting and learning.

In the journal Academy of Management Review, they argue that the positive or negative effects of stretch goals are mainly driven by two forces: the recent business performance of the organization and the presence of “slack resources.”

Firms with recent success are less likely to perceive an immediate threat, the researchers say, so if they undertake a stretch goal, they likely would be more open to new ideas and able to generate deeper learning. On the other hand, the researchers write, “if weaker recent performers choose to pursue a seemingly impossible goal, they are more likely to be overwhelmed by its demands and resort to hyper-vigilant, disorganized, or even frantic information processing that is disruptive to learning.”

“Slack resources” are uncommitted financial or other resources that are available for discretionary use by managers. Greater slack gives an organization the people, money, and time to reach and leverage stretch goals. Limited slack would have the opposite effect, they say, since detecting “novel recombinations” takes time and effort that are not available.

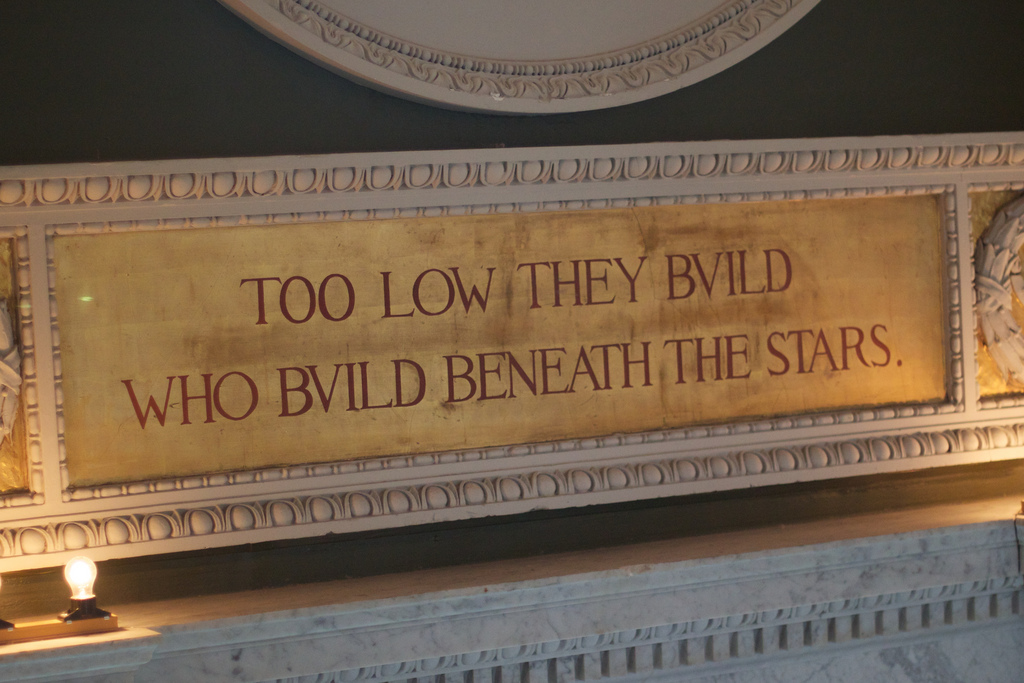

“Organizations most likely to benefit from stretch goals are least likely to use them”

But when the researchers considered what drives companies to actually adopt stretch goals, they came to surprising conclusions. They found that firms with stronger recent performance are more risk averse and therefore less likely to adopt stretch goals, in contrast to struggling organizations that are more willing to undertake risky actions. Similarly, firms with unabsorbed slack have been shown to have little motivation to take risks or adaptive measures.

It is a real paradox. “The organizations most likely to benefit from stretch goals are least likely to use them, and the organizations least likely to benefit from them are the most likely to use them,” the research team writes. “This pattern suggests that it is really only under quite limited conditions that organizations will be safely positioned to experience positive learning and performance outcomes from pursuing stretch targets — namely, organizations with both high slack resources and high recent performance.” Few organizations fall into that category.

So why do we continue to believe that stretch goals are a great idea? Sitkin et al point out that most famous stretch goal success stories come from organizations in which management set very ambitious performance goals to prepare for a radical change while the organization was flush with resources: IBM in the 1960s, General Electric in the 1980s, Toyota in the 1990s. “Proponents of stretch goals may have overgeneralized based on evidence from organizations that had substantial slack resources and, in many cases, also had strong recent performance.”

Sim Sitkin, Kelly See, C. Chet Miller, Michael W. Lawless, Andrew M. Carton; The paradox of stretch goals: organizations in pursuit of the seemingly impossible; Academy of Management Review (2011, Vol. 36, No. 3, 544–566)